On November 6, 2012, millions of citizens in the United States will elect or re-elect representatives in Congress. Long before those citizens reach the polls, however, their elected representatives and their political allies in the state legislatures will have selected their voters.

On November 6, 2012, millions of citizens in the United States will elect or re-elect representatives in Congress. Long before those citizens reach the polls, however, their elected representatives and their political allies in the state legislatures will have selected their voters.

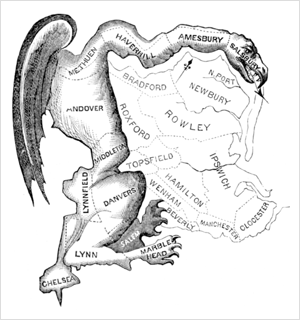

Given powerful new data analysis tools, the practice of “gerrymandering, or creating partisan, incumbent-protected electoral districts through the manipulation of maps, has reached new heights in the 21st century. The drawing of these maps has been one of the least transparent processes in governance. Public participation has been limited or even blocked by the authorities in charge of redistricting.

While gerrymandering has been part of American civic life since the birth of the republic, one of the best policy innovations of 2011 may offer hope for improving the redistricting process. DistrictBuilder, an open-source tool created by the Public Mapping Project, allows anyone to easily create legal districts.

Michael P. McDonald, associate professor at George Mason University and director of the U.S. Elections Project, and Micah Altman, senior research scientist at Harvard University Institute for Quantitative Social Science, collaborated on the creation of DistrictBuilder with Azavea.

“During the last year, thousands of members of the public have participated in online redistricting and have created hundreds of valid public plans,” said Altman, via an email. “In substantial part, this is due to the project’s effort and software. This year represents a huge increase in participation compared to previous rounds of redistricting — for example, the number of plans produced and shared by members of the public this year is roughly 100 times the number of plans submitted by the public in the last round of redistricting 10 years ago. Furthermore, the extensive news coverage has helped make a whole new set of people aware of the issue and has reframed it as a problem that citizens can actively participate in to solve, rather than simply complain about.”

For more on the potential and the challenges present here, watch the C-SPAN video of the Brookings Institution discussion on Congressional redistricting and gerrymandering, including what’s happening in states such as California and Maryland. Participants include Norm Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute and David Wasserman of the Cook Political Report.

The technology of district building

DistrictBuilder lets users analyze if a given map complies with federal and advocacy-oriented standards. That means maps created with DistrictBuilder are legal and may be submitted to a given’s state’s authority. The software pulls data from several sources, including the 2010 US Census (race, age, population and ethnicity); election data; and map data, including how the current districts are drawn. Districts can also be divided by county lines, overall competitiveness between parties, and voting age. Each district must have the same total population number, though they are not required to have the same number of eligible voters.

On the tech side, DistrictBuilder is a combination of Django, GeoServer, Celery, jQuery, PostgreSQL, and PostGIS. For more developer-related posts about DistrictBuilder, visit the Azavea website. A webinar that explains how to use DistrictBuilder is available here.

DistrictBuilder is not the first attempt to make software that lets citizens try their hands at redistricting. ESRI launched a web-based application for Los Angeles this year.

“The online app makes redistricting accessible to a wide audience, increasing the transparency of the process and encouraging citizen engagement,” said Mark Greninger, geographic information officer for the County of Los Angeles, in a prepared statement. “Citizens feel more confident because they are able to build their own plans online from wherever they are most comfortable. The tool is flexible enough to accommodate a lot of information and does not require specialized technical capabilities.”

DistrictBuilder does, however, look like an upgrade to existing options available online. “There are a handful of tools” that enable citizens to participate, said Justin Massa in an email. Massa was the director of project and grant development at the Metro Chicago Information Center (MCIC) and is currently the founder and CEO of Food Genius. “An ESRI plugin and Borderline jump to mind although I know there are more, but all of them are proprietary and quite expensive. There’s a few web-based versions, but none of them were usable in my testing.”

Redistricting competitions

DistrictBuilder is being used in several state competitions to stimulate more public participation in the redistricting process and improve the maps themselves. “While gerrymandering is unlikely to be the driving force in the trend toward polarization in U.S. politics, it would result in a significant number of seats changing hands, and this could have a substantial effect on what laws get passed,” said Altman. “We don’t necessarily expect that software alone will change this, or that the legislatures will adopt public plans (even where they are clearly better) but making software and data available, holding competitions, and hosting sites where the public can easily evaluate and create plans that pass legal muster, has increased participation and awareness dramatically.”

The New York Redistricting Project (NYRP) is hosting an open competition to redistrict New York congressional and state legislative districts. NYRP is collaborating with the Center for Electoral Politics and Democracy at Fordham University in an effort to see if college students can outclass Albany. The deadline for entering the New York student competition is Jan. 5, and the contest is open to all NY students.

In Philadelphia, FixPhillyDistricts.com included cash prizes when it kicked off in August of this year. By the end of September, citizensourced redistricting efforts reached the finish line, though it’s unclear how much impact they had. In Virginia, a similar competition is taking aim at the “rigged redistricting process.”

“This [DistrictBuilder] redistricting software is available not only to students, but to the public at large,” said Costas Panagopoulos in a phone interview. At Fordham University, Panagopoulos is an assistant professor of political science, the director of the Center for Electoral Politics and Democracy, and the director of the graduate program in Elections and Campaign Management. “It’s open source, user friendly and has no costs associated with it. It’s a great opportunity for people to get involved and have the tools they need to design maps as alternatives for legislatures to consider.”

Panagopoulos says maps created in DistrictBuilder can matter when redistricting disputes end up in the courts. “We have seen evidence from other states where competitions have been held,” he said. “Official government entities have looked to maps that have been drawn by students for guidance. In Virginia, students submitted maps that enhanced minority representation. There are elements in the plan that will be officially adopted.”

While it might seem unlikely that a map created by a team of students will be adopted, elements created by students in New York could make their way into discussions in Albany, posited Panagopoulos. “Our sense is that the criteria students will use to design maps will be somewhat different than what lawmakers will choose to pursue,” he said. “Lawmakers may take concerns about protecting incumbents or partisan interests more to heart than citizens will. At the end of the day, if lawmakers think that a plan is ultimately worse off for both parties, they may adopt something that’s more benign. That’s what happened in the last round of redistricting. Legislators pushed through a different map rather than the one imposed by a judge.”

For a concrete example of how the politics play out in one state, look at Texas. Ross Ramsey, the executive editor of The Texas Tribune, wrote about redistricting in the Texas legislature and courts:

The 2010 elections put overwhelming Republican majorities in both houses of the Legislature just as the time came to draw new political maps for state legislators, the Congressional delegation and members of the State Board of Education. Those Republicans drew maps to give each district an even number of people and to maximize the number of Republican districts that could be created, they thought, under the Voting Rights Act and the federal and state constitutions.

Or look at Illinois, where a Democratic redistricting plan would maximize the number of Democratic districts in that state. Or Pennsylvania, where a new map is drawing condemnation for being “rife with gerrymandering,” according to Eric Boehm of the PA Independent.

While redistricting has historically not been the most accessible governance issue to the voting public, historic levels of dissatisfaction with the United States Congress could be channeled into more civic engagement. “The bottom line is that the public never had an opportunity to be as involved in redistricting as they are now,” said Panagopoulos. “It’s important that the public get involved.”

Strata 2012 — The 2012 Strata Conference, being held Feb. 28-March 1 in Santa Clara, Calif., will offer three full days of hands-on data training and information-rich sessions. Strata brings together the people, tools, and technologies you need to make data work.

Strata 2012 — The 2012 Strata Conference, being held Feb. 28-March 1 in Santa Clara, Calif., will offer three full days of hands-on data training and information-rich sessions. Strata brings together the people, tools, and technologies you need to make data work.

Better redistricting software requires better data

Redistricting is “an emerging open-government issue that, for whatever reason, hasn’t gotten a ton of attention yet from our part of the world,” wrote Massa. “This scene is filled with proprietary datasets, intentionally confusing legislative proposals, antiquated laws that don’t compel the publication of shape files, and election results data that is unbelievably messy.”

As is the case with other open-government platforms, DistrictBuilder will only work with the right base data. “About a year ago, MCIC worked on a voting data project just for seven counties around Chicago,” said Massa. “We found that none of the data we obtained from county election boards matched what the Census published as part of the ’08 boundary files.” In other words, a hoary software adage applies: “garbage in, garbage out.”

That’s where MCIC has played a role. “MCIC has been working with the Midwest Democracy Network to implement DistrictBuilder for six states in the Midwest,” wrote Massa. According to Massa, Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio didn’t have anything available at a state level. Among these states, according to Massa, only Minnesota publishes clean data. Earlier this year, MCIC launched DistrictBuilder for Minnesota.

“The unfortunate part is that the data to power a truly democratic process exists,” said Massa. “We all know that no one is hand-drawing maps and then typing out the lengthy legislative proposals that describe, in text, the boundaries of a district. The fact that the political parties use tech and data to craft their proposals and then, in most cases, refuse to publish the data they used to make their decisions, or electronic versions of the proposals themselves, is particularly infuriating. This is a prime example of data ‘empowering the empowered‘.”

Image Credit: Elkanah Tisdale’s illustration of gerrymandering, via Wikipedia.

Related: